What does it feel like to age and live with dementia? These simulations can show you

What if you could truly feel what it's like to grow old — as your body slows down, your senses fade, and the world becomes harder to navigate — years before your own time comes?

At a Toronto simulation centre, that understanding becomes visceral, offering caregivers a powerful way to build empathy and gain deeper insight into the daily realities of those they care for.

"The people we put in this, are not frail, older adults, so they get to embody an experience that's different from their own, and we hope that it changes the way that they approach and interact with the people they work with," Meaghan Adams told The Current's host Matt Galloway.

Adams is the manager of simulation and virtual learning at Baycrest's Centre for Education and Knowledge Exchange in Aging, and she guided Galloway through the experience earlier this year.

She began by dressing him in a weighted jumpsuit, followed by tight bands wrapped around his elbows, knees and neck to restrict movement.

Next came goggles that blurred his vision, earplugs that muffled his hearing and gloves that dulled his sense of touch.

Once fully suited up, Galloway was given a cane and asked to walk to a bookshelf and pick out a book. His movements were slow and the physical discomfort was soon accompanied by emotional unease.

"There's a real anxiety," Galloway told Adams. "I can't perceive certain things ... there's other people around, but I don't know what's going on."

It's just one of the tools the centre uses to give people a sense of what it's like to age. They also have a tablet-based simulation that lets users experience life with dementia — like mistaking a robe on a bathroom door for a person, causing fear or confusion.

Older adults are the fastest-growing demographic in Canada. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research projects that by 2026, more than one in five Canadians will be seniors. By 2046, the number of Canadians aged 85 and older is expected to triple.

Aging doesn't automatically mean becoming feeble — but it does raise the risk of chronic illness, physical decline and cognitive impairments. Over 1.6 million Canadians currently live with frailty, which is projected to increase to more than 2.5 million in the next decade.

As well, the number of Canadians living with dementia is expected to climb by 187 per cent between 2020 and 2050, reaching over 1.7 million people.

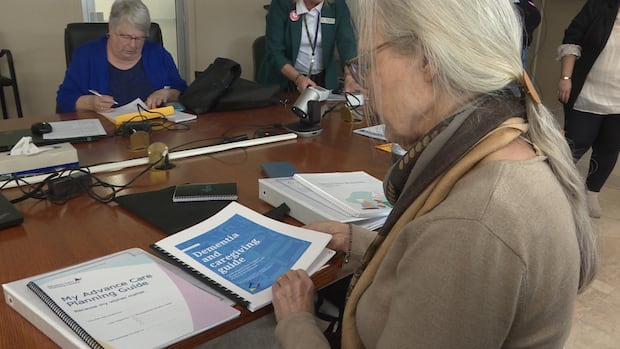

And as the number of people needing care increases, so too does the number of caregivers. One in four Canadians provide care to a friend, family member, or neighbour and half of Canadians will do so at some point in their lives.

Supporting caregiversAccording to Dr. Samir Sinha, director of health policy research at the National Institute on Ageing, caregiving for a loved one is a "24/7 job."

As such, empathy-building simulation tools, Sinha says, not only deepen understanding of those receiving care, but also highlight the challenges caregivers themselves face.

"We have to recognize that caregivers do need support and we should really focus on making sure that we can provide the necessary support in whatever way is possible," he said.

He says he works with a woman who has been caring for her husband with dementia for eight years. Sinha's role is to ensure she has the information, strategies and confidence she needs to handle complex and emotionally challenging situations.

The less knowledge a caregiver has, he says, the more stressful the experience becomes. Many caregivers suffer from anxiety, depression and physical health problems.

While emotional support is essential, he says practical assistance is just as important. That same caregiver's husband attends an adult dementia day program several days a week — giving her crucial time to rest and recharge, says Sinha.

Also, caregivers often spend thousands of dollars each year on out-of-pocket costs like transportation.

For Adams, simulations like those done at her centre are important for creating a more compassionate model of care.

In busy healthcare settings, it's easy for providers to focus on tasks and forget the person behind the diagnosis, she says. Adams believes empathy must be cultivated.

"We have to be intentional about giving people opportunities to … step back from the constant day-to-day rush and connect with why they're in the careers that they're in," said Adams.

"People are in healthcare because they value caring and helping others."

She says the simulations are designed to create a shift in perspective which for some people, can be visceral.

"Sometimes people get upset — they cry, because you feel something," said Adams. "You feel something that you wouldn't if I stood up in front of you and said, 'Older people have different hearing and different vision, and frailty looks like this.'"

That emotional connection, she says, helps everyone involved in care — staff, residents, families and friends — focus on the human being, not just the condition.

"They're a person with dementia, but they're a person, and they have preferences and histories and families and wonderful, rich, life stories," Adams said.

"If you can connect with that, you connect with the person that's still there."

cbc.ca