The planet is our farm: for every wild animal there are 10 for consumption or domesticated

For every wild animal, there are 10 domestic or edible animals. Humans now fly more than birds. Thirty percent of the whales that existed in 1850 remain in the seas. The total weight of cows has quadrupled since then. All remaining wild mammals have the same mass as the elephants of the 19th century. And only urban dogs, cats, and rodents weigh more than the rest of wild land animals. These could be answers to Trivial Pursuit, but these data are the result of two recently published scientific studies. One, in Nature Communications , compares domestic versus wild biomass. The other, in Nature Ecology & Evolution , measures how much humans move compared to other living beings. Both studies show how the human sphere has continued to grow at the expense of a retreating nature. This is one of the defining features of the Anthropocene .

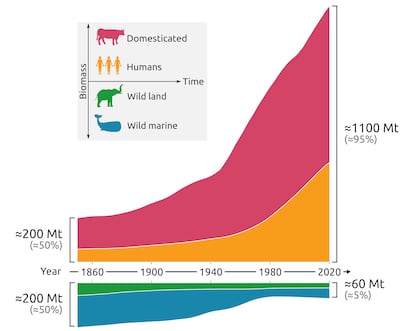

The first study compares the evolution of total human biomass and that of domesticated species with that of wildlife since 1850. The year is not arbitrary; it is when the Industrial Revolution became universal. The mathematical operation is relatively simple. To calculate how much humans represent, simply multiply the population by the average body mass. In the mid-19th century, there were about 1.2 billion people on the planet. Today, there are more than 8 billion of us. The average weight of a human today is 54 kilograms, but the authors estimate that body mass in the past was up to a third lower (due to the rise in obesity, but also to longer life expectancy, which increases the adult population). Taking everything into account, human biomass has multiplied eightfold, from 20 million tons to 420 million.

Humans wouldn't have gotten anywhere without their domesticated species. Therefore, the work adds to the human biomass the biomass of 14 domesticated species, such as cows, horses, and goats. They also add their desired companion animals, dogs and cats, and unwanted ones, mice and rats. In the first group, where cattle account for two-thirds of the total, only the biomass of horses has declined: after a peak in the 1920s, the arrival of trains and, above all, cars, pushed equines out of the way. In total, the mass of cattle, pigs, chickens, turkeys, ducks, and so on has quadrupled. Equally explosive is the growth in the biomass of companion animals, including rodents, which have gone from weighing around five million tons in 1850 to twenty million today.

Calculating the mass of wildlife is somewhat more complicated. Statistics for many species go back to 1850, but the case of whales helps scientists make their calculations. The whaling industry, traditional until the advent of innovations such as the steam engine and the explosive harpoon, became industrial in the mid-19th century, with very detailed records. The four largest whale species—blue whale, fin whale, humpback whale, and sperm whale—were nearly exterminated. Combined, all marine mammals weighed about 135 million tons in the mid-19th century. Today, it barely reaches 40 million.

Calculating the evolution of the biomass of the estimated 6,400 terrestrial mammal species is much more complicated. There are no records of what humans hunted or of the populations of each species that existed in the past, so the authors only provide estimates with a certain margin of error. The most reliable data available are limited to large predators, ungulates, and elephants. They used these data to make backward projections. They estimate that there were so many elephants in 1850 that they were equivalent to the entire biomass of remaining non-marine mammals. In total, they would have thinned from 50 million tons to about 20 million. In short, in the mid-19th century, animal biomass (including humans) was 400 million tons, half wild, half domestic. Today, it has almost tripled, but it has only grown on the human side, with mammals reduced to 5% of the current total.

“The new study reveals the extent of humanity's dominance over wildlife and how difficult it is to repair the damage we've caused to nature,” says Ron Milo , a researcher at the Weizmann Institute of Science (Israel) and coordinator of both studies. For Milo, the most surprising finding is the collapse of marine mammal populations. “These populations were severely damaged by industrial whaling, primarily in the mid-20th century. Although commercial whaling of large whales was banned about 40 years ago, their populations have only partially recovered,” he comments in a statement.

Beings in motionThe second paper analyzes a factor that has not been studied until now on a global scale: the movement of domestic versus wild biomass. The metric has the following formula: the total mass of a species' members multiplied by the distance they travel per year. For many of them, migration is vital, such as wildebeests or migratory birds, but all animals move to feed, find a mate, escape, or pursue. Some, such as the top feline predators or large herbivores, are the engineers that shape their respective ecosystems .

Global human movement today is 40 times greater than that of all wild land mammals, birds, and arthropods combined. The true extent of that figure is best understood by breaking it down by means of transport. Thus, humans already fly more in their airplanes than all the birds in the skies. Research shows that 65% of human biomass movement is by car or motorcycle and only 20% by foot or bicycle. Even so, human movement while walking is six times greater than that of all wild land mammals, birds, and arthropods combined. On average, each person travels about 30 kilometers per day by various means, slightly more than wild birds. By comparison, wild land mammals only travel about 4 kilometers per day.

“These studies, driven by curiosity, also have significant consequences,” Milo recalls in an email. “First and foremost, they allow us to directly compare animal activity with that of humans and better understand the true power relations between humans, a species, and the rest of the animal world,” he adds. They also have ecological relevance. As the researcher says, “animal movement is vital to numerous ecological processes, the health of ecosystems, and animal survival.” There are many examples: foraging, nutrient transport, pollination, the physical configuration of the environment through soil compaction… and, Milo concludes, “it affects evolution through the mixing of genes between populations.”

EL PAÍS