Can water pollution be detected by looking at the danger signals emitted by nature?

We have the case of red tides; a phenomenon that occurs naturally and produces an increase in polluting toxins in the waters.

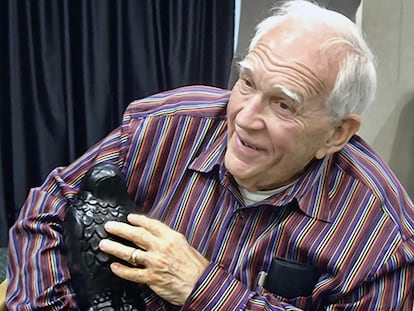

Wilbur Smith (1933-2021) was a bestselling adventure novelist who combined narrative action with luxurious and wealthy settings. In one of his novels, Like the Sea (Duomo), he introduces us to a biologist who works in a homemade laboratory set up on the coast, where she experiments with species that indicate marine pollution . To do so, she has set up a series of tanks that are very similar to glass aquariums, over which a complex scaffolding of spirals, bottles, and cables is projected.

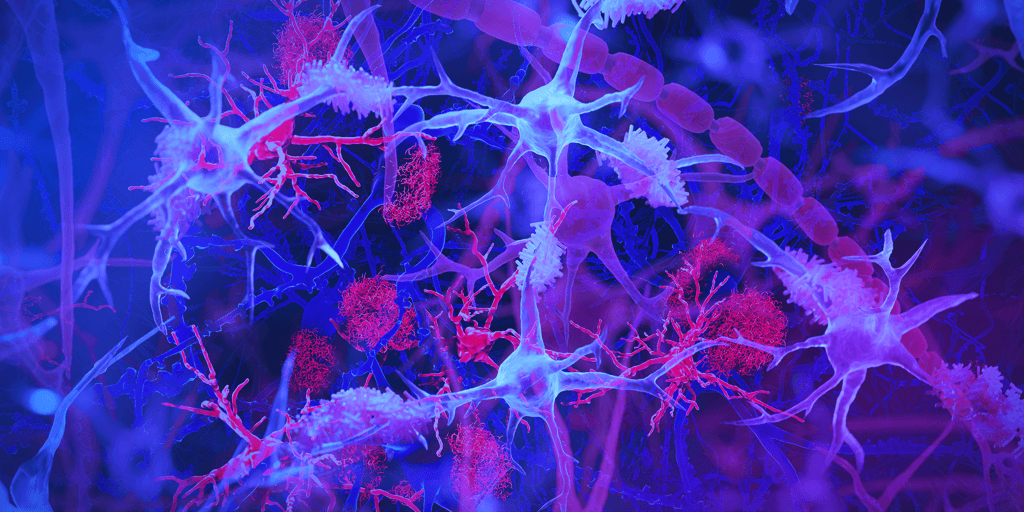

In this way, as she asserts, the cost is always lower than using spectrophotometric methods. It should be noted that these methods are very useful for detecting and quantifying metal contamination, not only in abundance but also at low concentrations. The spectrophotometer is an optical analysis tool that measures light absorption in a water sample. However, what the biologist's character is telling us here is that, in a rudimentary way, using the example of the clam that lives in one of the tanks— a Spisula solidissima— a very simple and rudimentary marine pollution detector is activated.

It's a method that taps into the wisdom of seafarers, people who go fishing and detect water pollution by interpreting nature's signs when they manifest in certain species , whether mollusks like mussels or crustaceans like crabs. For example, signs of toxicity include an increase in dead crabs or the nervous behavior of some fish due to algal blooms that deplete the oxygen in the water.

We have the case of the famous red tides , so called because the sea is tinged with this color, a toxic phenomenon that occurs naturally and produces an increase in microalgae that release contaminating toxins, as happened in Vigo when, in October 1976, there were poisonings by raft-fed mussels. Although there was no red tide during the days preceding the poisoning, a greenish glow could be seen - on some nights in August - along the coast of the Corcubión estuary. Apparently, the source of the poisoning was a single-celled organism called Gonyaulax tamarensis , a genus of toxic dinoflagellate that produces a paralyzing neurotoxin that penetrates the mussel tissues, as apparently occurred on the Galician coast in 1976; an event that becomes a literary figure if we pay attention to chance and its metaphors, since, while the greenish glow was taking place, Wilbur Smith was at his residence in South Africa writing the novel that concerns us today, a maritime story where ecology and water pollution - not precisely due to natural phenomena - dominate its reading as the plot between monetary selfishness and the defense of natural resources progresses.

Do you want to add another user to your subscription?

If you continue reading on this device, it will not be possible to read it on the other device.

ArrowIf you want to share your account, upgrade to Premium, so you can add another user. Each user will log in with their own email address, allowing you to personalize your experience with EL PAÍS.

Do you have a business subscription? Click here to purchase more accounts.

If you don't know who's using your account, we recommend changing your password here.

If you decide to continue sharing your account, this message will be displayed indefinitely on your device and the device of the other person using your account, affecting your reading experience. You can view the terms and conditions of the digital subscription here.

Journalist and writer. His notable novels include "Champagne Thirst," "Black Powder," and "Mermaid Flesh."

EL PAÍS