Bogotá and private universities account for the majority of cases of mistreatment in medical training, according to a report.

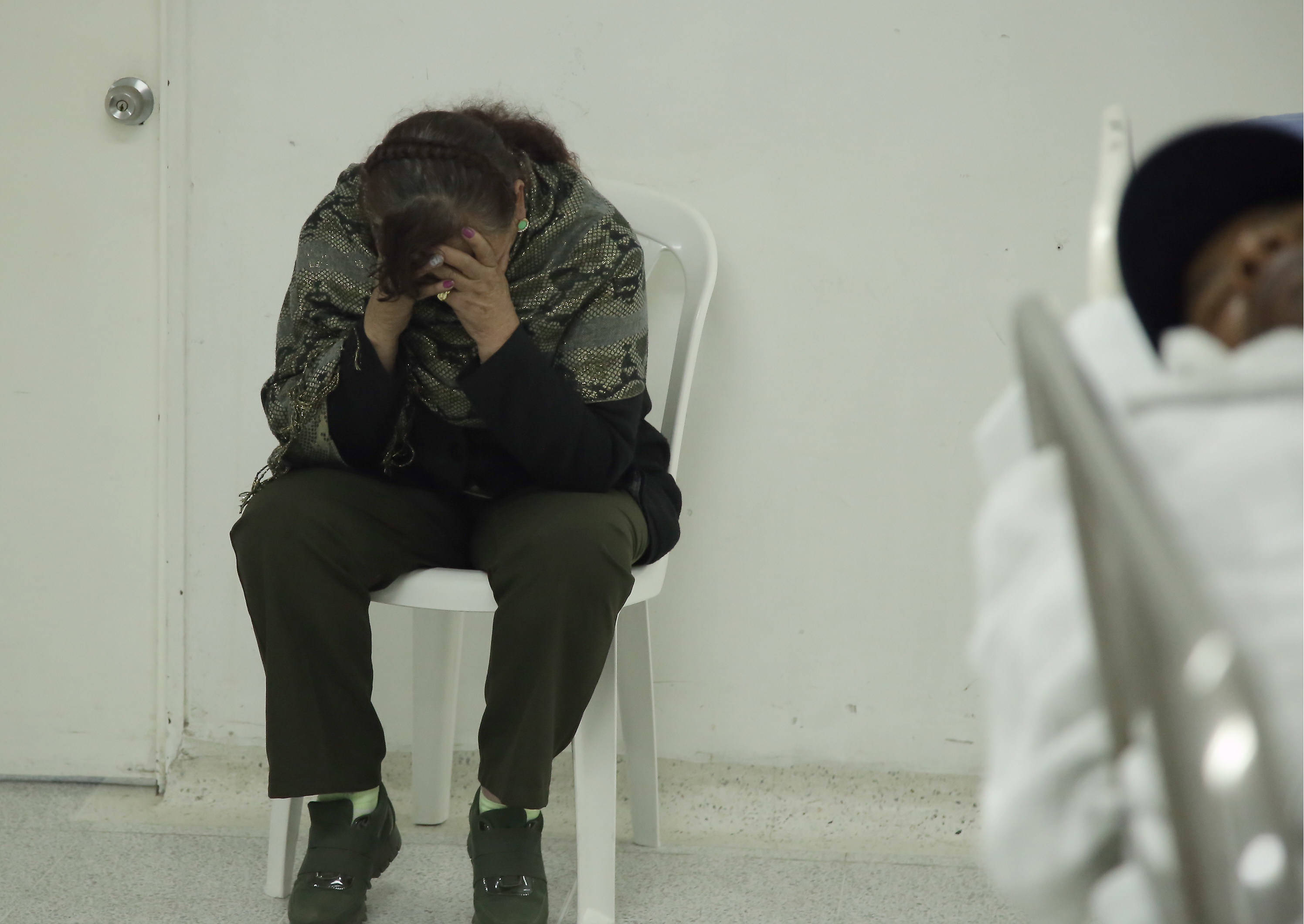

The death of resident physician Catalina Gutiérrez Zuluaga in 2024 marked a turning point in the discussion about the conditions of doctors in training in Colombia. Her death, which occurred while she was on residency rotations, starkly exposed a reality that many in the healthcare sector had been silently denouncing: excessive working hours, work pressure, harassment, and a lack of psychological support.

Catalina, who took her own life, was described by her colleagues as a dedicated and disciplined professional. She was part of a group of young doctors who faced weeks with up to 100 hours of accumulated work between hospital shifts, rotations, and on-call duties. Her case sparked outrage within the medical community and became a symbol of the struggle for improved working conditions for residents, interns, and medical students.

Pediatrics, General Surgery, and Gynecology are the areas with the most reports. Photo: Néstor Gómez - EL TIEMPO

Following her death, doctors from various cities launched a national mobilization under the slogan "No More Catas," which sought to highlight the physical and mental risks faced by medical students. This movement gave rise to the political impetus that led to the so-called Doctor Catalina Law, currently under review by the Senate's Seventh Committee.

A report that reveals the scope of the problem In this context, the National Association of Interns and Residents (ANIR) presented a report entitled "Mistreatment in medical training: characterization of complaints in undergraduate and postgraduate students in Colombia," which seeks to measure the magnitude of the problem in the country.

The document, prepared by Cindy Rodríguez, Juliana Moreno and Gabriel Martínez, systematizes 163 complaints from 11 cities, one municipality and 32 universities, and confirms that mistreatment in medical training is not an isolated or institutional phenomenon, but a structural one.

The cases were classified by type of violence, specialty, academic level, and location of the incident. Although the reporting channel was created for medical residents, complaints were also received from undergraduate students, interns, and students in other health fields, such as dentistry and speech therapy.

One in three reports of mistreatment comes from surgical specialties. Photo: César Mateus - EL TIEMPO

- 124 corresponded to verbal abuse

- 123 to psychological violence

- 64 to work overload

- 20 to gender-based violence

- 12 to physical abuse

- 11 to sexual harassment

- 5. Discrimination based on race, sexual orientation or place of origin

- 2 to direct workplace harassment

The complaints originated primarily from Bogotá (103 cases), followed by Cali (17) and Medellín (15). Cases were also reported in Bucaramanga, Barranquilla, Cartagena, Neiva, Pereira, Manizales, Tunja, and Popayán. The majority of the incidents occurred in surgical (89 cases) and medical (59 cases) residency programs.

Bogotá and private universities lead the list. Photo: Néstor Gómez - EL TIEMPO

The specialties with the highest number of complaints were:

- Pediatrics (16 cases)

- Gynecology and Obstetrics (16)

- General Surgery (15)

- Orthopedics (11)

- Anesthesiology (9)

- Otolaryngology (8)

- Internal Medicine (7)

- Psychiatry (7)

- Plastic Surgery (6)

- Family medicine (5)

- Neurosurgery (4)

The study also revealed differences between public and private universities: 97 complaints originated from private institutions, 60 from public ones, and 6 had no data available. Bogotá had the highest concentration of universities with the most reports, with up to 24 complaints against a single private institution.

According to the authors, mistreatment manifests itself in different ways: from the abuse of power by teachers and tutors, the normalization of verbal humiliation, the excessive workload without fair remuneration, to sexual harassment and the exclusion of those who refuse to follow hierarchical patterns.

“Most complaints describe learning environments where obedience is prioritized over holistic development and well-being. Many residents work shifts exceeding 100 hours per week without psychological support or rest areas,” the document reads.

For Cindy Rodríguez, former president of ANIR and one of the authors of the report, the problem is rooted in medical culture and is perpetuated under the idea that suffering forges better professionals.

“Violence has become normalized in medical training. Students are taught that to be good doctors they must endure mistreatment, sleep little, and suffer humiliation. This is unacceptable and has serious consequences for their mental health and the quality of their care,” Rodríguez explained.

According to the doctor, the study aims not only to highlight statistics but also to "open a conversation about the human cost of medical excellence." She added that 7% of the complaints analyzed mention suicide attempts or suicidal ideation related to pressure and mistreatment, a figure she described as alarming.

Rodríguez argued that Dr. Catalina's case served as a turning point: “Catalina didn't die solely from physical exhaustion. She died in a system that fails to protect those who train the doctors of the future. That's why the Dr. Catalina Law is not just a tribute; it's a debt owed to the entire profession.”

The former president of ANIR also warned that the lack of clear protocols for reporting aggravates the situation, as many students fear reprisals or academic sanctions.

“In some hospitals, if a resident reports mistreatment, they risk losing their rotation or not graduating. That's why we're asking for the law to guarantee anonymous reporting channels and real sanctions for institutions that allow it,” he added.

The Dr. Catalina Law: towards a dignified environment for residents In response to these findings and pressure from the union, Congress is moving forward with the processing of the Doctor Catalina Law, which has already been approved in the second debate in the House of Representatives and is currently being discussed in the Seventh Committee of the Senate.

The initiative, promoted by Congresswoman María Fernanda Carrascal (Historical Pact), seeks to regulate working hours, strengthen mental health programs and guarantee dignified conditions for resident physicians.

Among its main points, the law proposes:

- Limit the working day to 12 hours per day and 60 hours per week, avoiding long shifts without rest.

- Implement wellness and mental health programs for residents in hospitals and universities.

- Guarantee access to insurance and social benefits, which are currently non-existent or unequal.

- Create effective channels for reporting harassment, mistreatment or discrimination.

- Establish mechanisms for supervision and support during medical training.

- Sanction institutions that fail to comply with the provisions or allow environments of abuse.

- Support the return of Colombian residents abroad, to strengthen the national health system.

- The law also seeks to establish a culture of humanized medical training, in which tutors, universities, and hospitals share responsibility for the well-being of students.

“The Doctor Catalina Law represents a decisive step towards dignifying medical residency and a concrete response to a demand that has been going on for years,” Carrascal stated during his speech in the plenary session a few months ago.

If approved by the Senate, the Dr. Catalina Law could become one of the most significant reforms in health and medical education in the last decade. According to the National Association of Innovators and Rationalizers (ANIR), its implementation must be accompanied by strict oversight and resources for mental health, as the law will be useless without a change in institutional culture.

“Political will is needed, but so is empathy,” Rodríguez concluded. “Catalina cannot be just a name in a law; she must be the starting point for a more humane medicine, where learning doesn’t mean suffering.”

Environment and Health Journalist

eltiempo