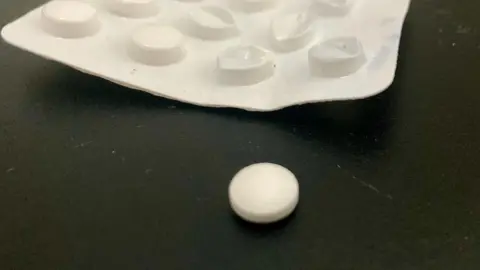

Low aspirin dose 'cuts cancer risk in some people'

A study to find the right dose of aspirin to reduce the risk of cancer in some patients has found the smallest amount works just as well as larger ones, according to a leading researcher.

The trial involved 1,879 people with Lynch syndrome who were given three different-sized doses of the painkiller.

Prof Sir John Burn, from Newcastle University, said he would ask health regulators to formally advise a low dose of 75mg be prescribed to those with the genetic condition, which puts them at a greater cancer risk.

Nick James, who has Lynch syndrome - and who has lost nearly all of his family to cancer - was the first person to sign up to the trial. He said the findings were "massively reassuring".

The furniture maker, based in Newcastle, no longer has any family left alive in the UK.

"Quite a few members of my family have had cancer - like colorectal cancers, or endometrial," he explained.

"My grandfather had bladder cancer, my mum had a certain kind of cancer. When you start looking at the family tree - it becomes quite apparent what's going on.

"We didn't actually know it was Lynch syndrome until 13 years ago, and that's when I learned about the aspirin trials."

To try and stop himself from developing cancer, Mr James was the first person to sign up to the latest trial nearly 10 years ago.

The Cancer Prevention Project 3 study (CaPP3), supported by Cancer Research UK, involved patients taking a different daily dose of aspirin: 100mg, 300mg or 600mg.

In the trial, a European-sized dose of 100 mg aspirin was used. The established dose is 75mg per day in the UK, and 81mg in the US.

It was only at the end of the study that Mr James learned he had been put on a 300mg dose.

"The fact that I can now go down to a baby aspirin makes it feel less scary," he said. "I didn't have any major side effects - but it potentially reduces any.

"That the research has shown that taking an aspirin reduces your risk of getting a cancer if you have Lynch syndrome is massively reassuring for me - and my family."

People with Lynch syndrome have inherited a faulty gene which can increase their chances of developing some cancers - including bowel and womb cancer.

Prof Burn, who was involved in discovering Lynch syndrome and who led the international study, said he focused his research on those patients "because they get so many cancers".

"We already have NICE guidance saying people with Lynch syndrome should be recommended to take aspirin. Now we should recommend a baby aspirin."

An earlier study led by Prof Burn found a protective effect in those taking 600mg of aspirin every day for just over two years.

He said the new results showed the lowest dose worked just as well as the larger doses.

"So what we can now say with statistical confidence is that the people taking a baby aspirin are as protected as the people taking two aspirins - but also much less likely to have side effects," he added.

In some people, aspirin can cause bleeding, so Prof Burn said he wanted health regulators to now recommend the lowest dose be given to Lynch syndrome patients.

"Roughly speaking, if someone with Lynch syndrome has about a 2% a year chance of getting mostly bowel cancers, we think if they take aspirin, that is halved - down to about 1% a year," he explained.

Prof Burn said the next big challenge was to find those who were unaware they even have Lynch syndrome.

He said "about 150,000 patients in the UK" have the condition, but a small number are only tested when they realise cancer runs in their family.

"It was only when they get cancer in their 40s and 50s, and remember their auntie had cancer, and their granddad."

NHS England said with only 5-10% of patients diagnosed, identifying more people with Lynch syndrome was a strategic priority. Once diagnosed, they can then be offered cancer screening and monitoring.

Prof Burn said: "We can also put them on to a baby aspirin - and cut their risk."

The findings of the study will be presented at the Cancer Prevention Research Conference, taking place in London from Wednesday, in partnership with the American Cancer Society.

BBC