Sally Ride, the pioneering astronaut who had to hide her lesbian status to reach space.

“Oh, by the way, Sally Ride was gay.” That was the headline New York Magazine gave to its story on the death of America’s first female astronaut on July 23, 2012. The headline was meant to emphasize the low-key, casual way in which the world learned both that the pioneer had died—of pancreatic cancer—and that she was a lesbian. A word in a press release, carefully crafted by her and her partner, which only mentioned in passing “Tam O'Shaughnessy, her partner for 27 years,” was almost bigger news in the US than the death of its first woman in space, a milestone achieved in 1983 (two decades after Valentina Tereshkova with the USSR). National Geographic premieres tomorrow, Tuesday, June 17, a documentary ( Sally , Disney+ ) that rediscovers her figure and the double difficulty the pioneer faced in achieving her goal: reaching space as a woman and a lesbian in an era as sexist as it was homophobic. A documentary that, by reviewing the pioneer's hardships, especially challenges today's society, now that many, like Donald Trump at NASA, want to erase all traces of diversity or empowerment of minorities on their path to real equality.

“Every kid dreamed of being an astronaut at some point, but since the space program was all-male, it never even occurred to me that I could be one,” Ride begins in the film, which is constructed from footage from his time at the space agency and current accounts from people close to him, like his widow, Tam O'Shaughnessy.

Fortunately, in 1976, NASA opened its doors to the first class that accepted women and racial minorities, and Ride, born in Los Angeles in 1951, didn't hesitate to apply. She was an astrophysicist at Stanford University and an amateur tennis player with the chops to have been a professional, in case anyone was wondering about meritocracy. In the presentation of that class of 35 candidates, only 10 got all the spotlight and hours of excruciating press questions: the six women, three Black men, and one of Asian descent. They got the worst of it. "They didn't want to know about our hopes for space exploration or what we wanted to do. They took the stereotypical perspective: the romantic, the makeup, the fashion... The perspective they usually used when reporting on women," recalls one of the candidates from that group, Kathy Sullivan.

“The only bad moments during training had to do with the press,” Ride recalls. And it’s easy to believe, given the pitiful questions she and her colleagues were asked in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Questions about motherhood, pregnancy, or whether she “cries” under pressure—this was even before she was about to fly into space. As the documentary clearly shows, these women wanted to fit in with the program, but at the same time, they were brave and successful professionals who didn’t flinch when it came to standing up to the sexism of the time. “You shouldn’t even ask that question, just delete it,” Judith Resnik tells a reporter. “Either call me Dr. Ride or Sally,” the astronaut tells another reporter who calls her “Miss Ride.”

Competitive and ambitious, like anyone aspiring to go into space, Ride knew just what to say in front of the cameras to avoid making a fool of herself. “Are there people at NASA who don't think women are ready?” she was asked. “I think there are some people who are just waiting to see how I do it. Let me put it that way.”

But the truth is that the pressure was at its highest, at the Johnson Space Center, where there were 4,000 men and four women. A place named in honor of Lyndon Johnson, the man who nipped the Mercury program in the bud in the 1960s, which aimed to train female astronauts at the dawn of the space race. The race the Soviets won four times with Sputnik , Laika , Yuri Gagarin, and Tereshkova. And also with Svetlana Savitskaya , the second woman in space, in 1982.

NASA's "man culture" was on display in a now-legendary episode, narrated by Ride herself in the documentary. She was the first woman to check what they called "crew equipment," the space toiletries bag. They already knew what to pack in the men's, but what to pack in hers? "In their infinite wisdom, NASA engineers designed a makeup case," Ride says bluntly: little pockets for lipstick, eyeliner, makeup remover... "Then they asked how many tampons they should carry on a week-long flight. 'Is 100 the right number?' I said no, it wasn't the right number."

“Sally grabs one of those toiletry bags, a canvas bag with zippers, and keeps pulling out tampons like those funny snakes that jump out in party tricks,” Sullivan recalls. “The six of us together, in half a year, wouldn't have used all the tampons in there.”

When Sally's mother was asked to comment on the historic change that had allowed her daughter to become an astronaut, she exclaimed , "God bless Gloria Steinem!" referring to the historic feminist, who also attended her launch into space in 1983 as a VIP . But Ride was mostly low-key, defending her place as a woman without openly declaring herself a feminist (although she did have a historic conversation with Steinem ). Upon returning to Earth, as the most famous woman in the world, she felt the anxiety, the weight of being a role model—"women cried when they saw me"—and had to go to therapy to deal with it.

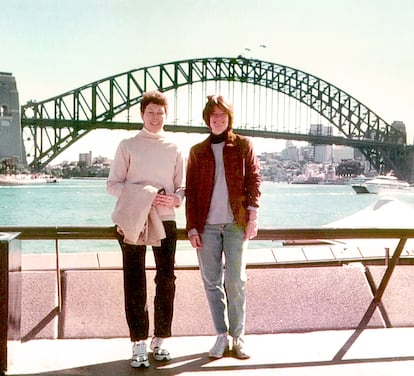

She met Tam during tennis lessons as a teenager, with whom she developed a close friendship that blossomed into true love in 1985, shortly after returning from space. In 1982, before being selected for that mission, she had married a classmate, Steven Hawley, who appears in the documentary acknowledging: "We were more like roommates than life partners." Ride divorced both her husband and NASA in 1987, after discovering after the Challenger accident (in which her friend Resnik died ) that the agency wasn't doing everything it should have to protect its crew.

The astronaut hid her homosexuality until her death—"I was afraid, and it breaks my heart," her widow now says—and she had good reason to do so. Her friend and famous tennis player Billy Jean King explains in the film the exemplary impact it must have had on Ride when she herself was dragged down the walk of shame in the early 1980s after being discovered as a lesbian, losing public favor and millions in contracts.

At the end of the documentary, a friend of Ride's laments: “I found out [she was a lesbian] almost at the same time as the rest of the world: when I read her obituary. I was saddened that society could make someone we admire, love, and respect feel like she had to hide something about herself.”

“Sally had to repress a large part of her identity in order to break the highest glass ceiling,” says Cristina Costantini, the documentary’s screenwriter and director, who warns, citing the current Trump administration, that “many of our hard-won rights are once again under threat.” A few weeks ago, NASA removed from its website the stated intention of having a woman step on the Moon on the next manned trip to the satellite, removing the last remaining glass ceiling for female astronauts. Until the next Sally Ride manages to break it.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F127%2F83e%2F76c%2F12783e76cd33b894a8f3d5207db800a7.jpg&w=1280&q=100)