Climate change put an end to the megasite culture 4,300 years ago.

The phenomenon known as Climate Event 4.2 ka BP was one of the most decisive environmental periods of the Holocene (the last 10,000 years) on the Iberian Peninsula. Temperatures rose by two degrees between c. 2400 and 2250 BC, while a prolonged drought was experienced. In the southern peninsula, there was "environmental degradation with the depletion of forest resources, the expansion of Cistaceae and Ericaceae thickets, an abrupt reduction in pine trees, a decrease in oak and cork oak trees, and a sharp increase in holm oaks," according to the study "Time, Sustainability, and Collapse in the Large Settlements of the Copper Age in the Iberian Peninsula," written by Professor of Prehistory Leonardo García Sanjuán and geographer Francisco Sánchez Díaz, both from the University of Seville.

The article, published in the Journal of Urban Archaeology, indicates that this environmental factor ― combined with other economic, social and demographic factors ― caused the complete disappearance of one of the most unique cultures in the history of the Iberian Peninsula, that of the megasites of the Copper Age or Chalcolithic, enormous settlements that acted as central places of power and religiosity interconnected by means of trade and knowledge.

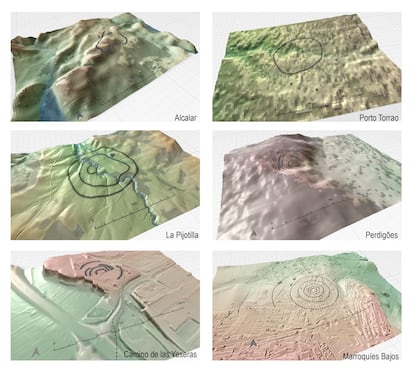

At the beginning of the third millennium BC, a new type of settlement emerged on the Iberian Peninsula. Given their enormous size (tens or hundreds of hectares), these settlements are known as "megasites." So far, seven have been located on the Iberian Peninsula: Alcalar, Perdigões, and Porto Torrão in Portugal; and Camino de las Yeseras, Marroquíes Bajos, La Pijotilla , and Valencina in Spain . All of them were built on flat terrain, near fast-flowing rivers, on highly fertile soils, delimited by ditches arranged in concentric circles, and housing scattered structures within them without prior planning or organized plans.

Its enormous size was its most notable feature. The largest found so far is located in Valencina de la Concepción (Seville) and spanned some 450 hectares. "No civilization, until the Roman period, would ever again generate such enormous settlement structures on the peninsula," the experts explain.

García Sanjuán and Sánchez Díaz have concluded that not all megasites lasted the same amount of time. While their average lifespan was around a thousand years, some, like Perdigões, survived 15 centuries. "This extremely long lifespan of Iberian Copper Age megasites, exceptional when compared to other megasites worldwide, is indicative of the remarkable level of sustainability achieved by these societies," they say.

Like all cultures, and given their enormous temporal durability, these large settlements experienced cycles of growth, crisis, recovery, decline, and abandonment. "These periods of crisis and recovery indicate that their social system enjoyed a high degree of resilience," they assert. For example, around 3200 BC, the settlements of Alcalar, Valencina, Porto Torrão, Perdigões, and La Pijotilla significantly intensified their activity, while between 2700 and 2600 they experienced a major crisis from which they would take almost a century to recover. And by around 2200 BC, most of the megasites fell into disuse. This abandonment was gradual, except in the case of Valencina, where the cessation of activity occurred more abruptly.

And what caused this major crisis? In addition to the aforementioned temperature increase, three periods of severe cooling were recorded, which had a "very negative" impact on economies based on wheat and barley. During this period, Climate Event 4.2 developed, with a drastic reduction in rainfall, "a decisive and even final factor in instability." This environmental degradation thus led to the "depletion of forest resources, noticeable in the south of the Iberian Peninsula throughout the third millennium, with the expansion of scrubland."

It is likely that late Copper Age societies attempted to respond to warming and drought by intensifying production, although the data on this matter are still ambiguous. What seems clear is that "they were unable to overcome the breakdown of the exchange networks that gave meaning and social function to the megasites."

In parallel, starting around 2500 BC, a major demographic shift occurred, leading to the widespread replacement of male haplogroups (DNA modifications that define human groups) present since the Neolithic by others arriving from Europe. Surprisingly, this shift did not affect female lineages. "Although this male replacement has sometimes been defined as an 'invasion,' the chronology of the process reflects a slow penetration, since it lasted six centuries between c. 2500 and 1900 BC, with a northeast-southwest gradient. This process of demographic penetration was completed in the Early Bronze Age, during which genomic data reflect a male reproductive monopoly of the new haplogroup, called M-269 by geneticists."

The confluence of all these factors led to the end of the gigantic, ancient sites that had articulated social life in the Neolithic and Copper Ages, including the system of "networks for the exchange of exotic materials, shapes, and symbols in luxury crafts made of amber, ivory, cinnabar, copper, gold, variscite, rock crystal, ostrich eggs, and ceramics." All of this was replaced by "a monotonous discourse of power, supported by the constant display of new copper and bronze weapons as symbols of the elite."

Despite the relatively rapid collapse of sites like Valencina, as a population and social phenomenon, Iberian megasites appear to have been quite resilient and sustainable as focal points of Chalcolithic social life, functioning as meeting places for many centuries. This prolonged occupation was unmatched by any other type of settlement during European prehistory.

EL PAÍS

%3Aformat(png)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F577%2F9bf%2Fa7d%2F5779bfa7de36dad69330146bcf213074.png&w=1280&q=100)

%3Aformat(jpg)%3Aquality(99)%3Awatermark(f.elconfidencial.com%2Ffile%2Fa73%2Ff85%2Fd17%2Fa73f85d17f0b2300eddff0d114d4ab10.png%2C0%2C275%2C1)%2Ff.elconfidencial.com%2Foriginal%2F0c3%2Fa12%2F03e%2F0c3a1203ed26b58b5634ed63c50674d3.jpg&w=1280&q=100)